An investment strategy for population health

18 February 2020

Healthcare is eating other public service funding so says the ex-editor of the BMJ.

This blog from Mathew Whittaker sets out how the austerity policy and political priorities pursued by successive governments have placed major strain on a number of public services.

He argues that, as a result, the size of the state has changed over the past decade and so too has its shape.

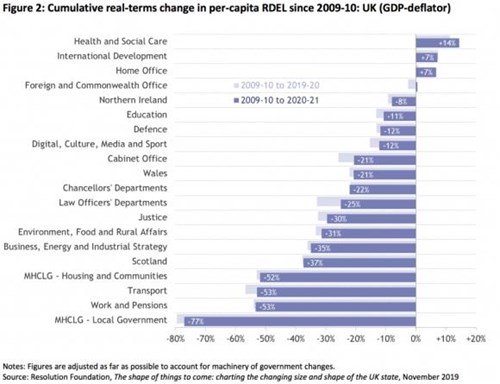

“Local government budget is on course to have been cut by 77% in 2020-21 relative to a 2009-10 baseline when measured on a per-capita basis. Other departments have fared only a little better, with real-terms per-capita spending down by a half in Housing and Communities, Transport and Work and Pensions, and by a third in Scotland, BEIS, DEFRA and Justice.”

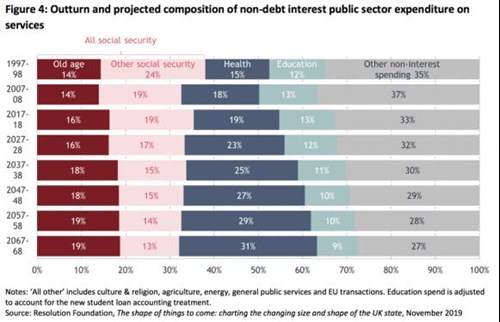

It is worth noting the changing proportions of government spending to “health” (the NHS) out to 2070.

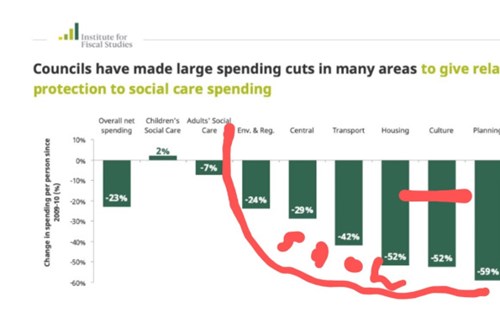

The IFS analysis of local government spending highlighted broadly the same story. Of course it was an analysis of local government thus included locally raised revenue. Thus the numbers look different. Statutory services have (rightly) been relatively protected. Non statutory functions, of note include many of the place shaping and regulatory functions have not. One might only wonder what impact this has on our health. As a colleague of mine once pointed out, the services that we have cut furthest are basically the social determinants of health.

We know from plenty of analysis (IFS / NEF / JRF to name a few) that recent changes in spending and welfare have disproportionately disadvantaged those who are more vulnerable – at individual, family, community and city level.

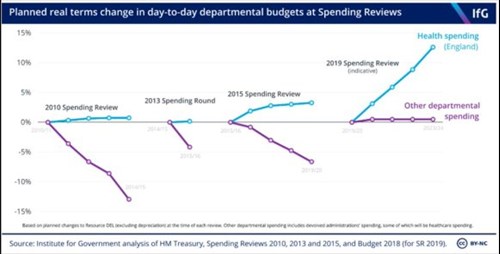

Smith pointed out that overall health care account for about 7% of the economy, that proportion having doubled over 40-50 years, pensions for 5%, and social care for 1%. In terms of public expenditure, spend on NHS has increased from 25% of public expenditure to 40% in last 20-30 yrs I had posted a thread on the “hegemony of health” a while ago. On past history, the ever increasing spend on “health” (by which most mean the NHS) isn’t set to deliver more “health. It simply displaces other investments that have a greater impact on health (and the may dampen ever increasing demand for care). The crowing out is self-accelerating. Back to my opening statement, health care expenditure is eating other public service spending. It is easy to argue that disinvesting in what actually generates health lead to preventable misery and spiralling healthcare costs? As has been pointed out “A national, natural experiment (ethics pending) “

Wanless told us this 20 years ago, everyone ignored him. Not addressing this will simply lock in ever upward spiraling % of GDP devoted to NHS.

There IS a need to reframe, “health” and “health inequalities” seem enduringly “stuck” as an NHS issue, or at best an issue that not (only) will be solved by better or more health care services whilst the narrative is often (usually) in the right place nobody is making investments in “the determinants” of health.

Within the NHS the power base and resource base is set all wrong for optimal population health between the NHS and wider potential investments the resource and power base is also set wrongly for optimal population health. There are distortions in resource distribution & attention that over prioritise process indicators over population health outcomes & hospital-based care over prevention, community & primary care.

This isn’t good for our health; I would encourage you to read health economics 101, especially about opportunity cost and the law of diminishing marginal returns. Again, Richard Smith set this out 6 years ago as did Don Berwick who was then in charge of the world’s largest health care system. The three most important things that health economics can give us are those or opportunity cost the law of diminishing marginal returns and incremental cost effectiveness analysis. We are VERY good at ignoring all of them.

This is all good news if you’re in med tech not so good news if you actually want substantial population health improvements.

Unchecked, the future NHS budget will be enormous – this isn’t necessarily good for our health and simply sets up a self-fulfilling cycle. Of course that matters for social care and NHS demand. Wanless eloquently demonstrated this two decades ago (we ignored him….). It also matters to economic productivity, I have posted some comment on this one already and there is more to follow.

Any serious attempt to improve health has to engage with this, whether locally or nationally. It has to be a truly cross government affair, not something that starts with the NHS and never quite gets out of that, and we should put our money where our mouth is.

Greg fell is Director of Public Health at Sheffield City Council